In the 1960s, the USA launched a recruitment policy to help drive up numbers for the Vietnam War. The Defense Secretary, Robert McNamara, unveiled Project 100,000 which would permit lower recruitment standards to allow applicants who would or had otherwise been rejected on medical and mental health grounds. The plan increased eligibility to people with what was considered low IQ (<91) entry into the military and was billed as a way to bring disadvantaged youth, comprising recruitment rejects and substandard volunteers, out of poverty and give them skills, aptitudes and benefits for their return to civilian life.

The project was a success in that it recruited more than 354,000 soldiers but that’s where the success ended. Despite having political backing from then President Lyndon B Johnson, military officers largely did not comply with the orders. Many of the recruits were passed through without receiving the training promised. By the end, less than 6% of Project 100,000 recruits received the training originally proposed. The difference in capability was clear for all to see because when compared to their peers, they were eleven times more likely to be reassigned and between seven and nine times more likely to require remedial training. Not surprisingly, they quickly earned the moniker of McNamara’s Morons. As was the case, they were unlikely to qualify for a technical trade meaning more than half were then sent into combat – something not mentioned by McNamara or recruiters.

The project was a success in that it recruited more than 354,000 soldiers but that’s where the success ended. Despite having political backing from then President Lyndon B Johnson, military officers largely did not comply with the orders. Many of the recruits were passed through without receiving the training promised. By the end, less than 6% of Project 100,000 recruits received the training originally proposed. The difference in capability was clear for all to see because when compared to their peers, they were eleven times more likely to be reassigned and between seven and nine times more likely to require remedial training. Not surprisingly, they quickly earned the moniker of McNamara’s Morons. As was the case, they were unlikely to qualify for a technical trade meaning more than half were then sent into combat – something not mentioned by McNamara or recruiters.

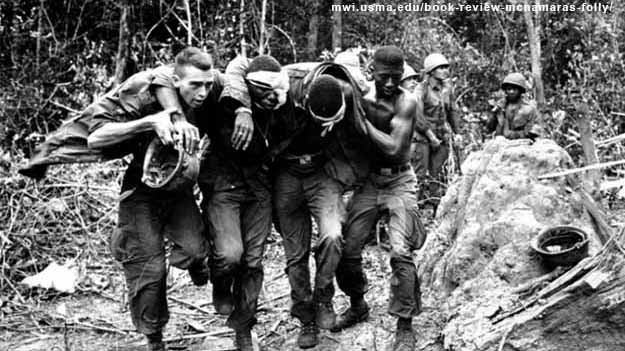

The consequences were dire. The troops recruited under Project 100,000 were three times as likely to be killed in action as their peers with 5,478 deaths recorded and another 20,270 wounded in Vietnam. The inability to follow simple commands, language barriers and increased risks to safety of other troops had further consequences. Not only were they bullied, they often received more dangerous roles such as sweeping for mines ahead of their unit. As one infantry unit leader said, “If anybody has to die, better a dummy than the rest of us”.

Having to live with traumatic experiences after the war and roughly half, or 180,000, being dishonourably discharged for minor issues meant their troubles continued post-service. As many employers were only willing to take on veterans who were honourably discharged, many of the recruits were more likely to have lower employment rates and incomes than their peers and were denied promised benefits such as housing assistance, healthcare with many ending up experiencing homelessness. This policy was a significant failure and should not be repeated.